MELINDA: Welcome to Leading With Empathy & Allyship, where we have deep, real conversations to build empathy for one another, and to take action to be more inclusive, and to lead the change in our workplaces and communities.

I’m Melinda Briana Epler, founder, and CEO of Change Catalyst and author of How To Be An Ally. I’m a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion speaker, advocate, and advisor. You can learn more about my work and sign up to join us for a live recording at ally.cc.

All right, let’s dive in.

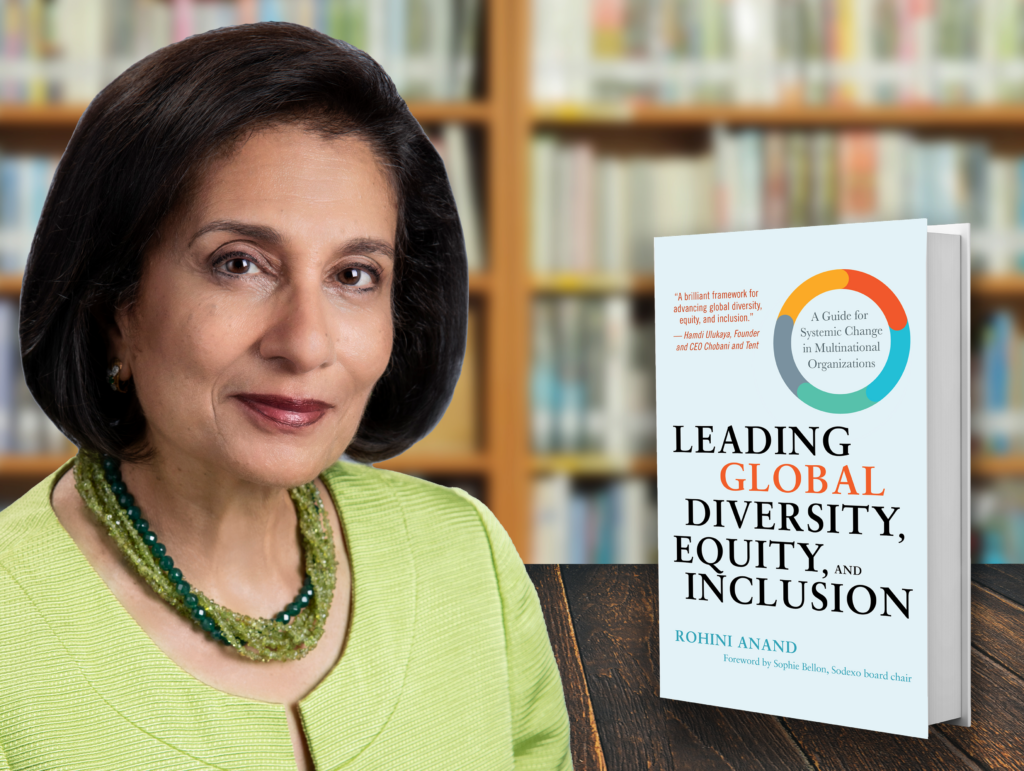

MELINDA: Hello, everyone. Today, our guest is Rohini Anand, Principal, and CEO of Rohini Anand LLC, and author of Leading Global Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion: A Guide for Systemic Change in Multinational Organizations. I have found her book to be incredibly useful as we do our global diversity, equity, and inclusion work. So, we’ll be talking about global diversity, equity, inclusion, and allyship together. Welcome, Rohini.

ROHINI: Thank you, Melinda. Excited about our conversation.

MELINDA: Likewise. Likewise. Let’s start by learning a little bit about you. Would you tell us a bit about your story, where you grew up, and how you came to do the work you do today?

ROHINI: Yeah. So thanks for that question, Melinda. I mean, you know as well as anyone else that anyone who does DEI work or diversity, equity, and inclusion work. It’s just very personal for them. My story is very integral to who I am. I grew up in Mumbai, India, where pretty much everyone looked like me. Of course, there were sort of many variations there, but I belong to the majority religion, Hinduism.

Surrounded by others like me, I had the privilege of not having to think about my identity. I moved to the United States as a single immigrant woman. This move was really sort of an inflection point in my journey, both literally and metaphorically. My identity shifted from being a person who saw herself at the center of her world to being a minority, to being an immigrant, and to being a foreigner.

Honestly, Melinda, I was completely unprepared for that. It was only when I was identified as a minority did I realize the privileges that I had as being part of a majority growing up in India. I was part of the majority, and I hadn’t recognized my privilege in that way. And honestly, I was unable to until I was perceived as a minority, and I experienced things differently.

The realization that identity is fluid, that it’s situational, has informed my research, and it continues to inform my work today. So, this vocation, DEI work, change, and transformation work, is very personal to me. And understanding of what it means to be perceived as an outsider, as a minority, is very much at the heart of DEI work. So, I like to say that today, my vocation and my avocation are perfectly aligned. I am in a place where I’m meant to be.

MELINDA: Fantastic. Can you say a bit about your work and what you do now, what you’ve done over the last many years?

ROHINI: Yeah. I actually was at Sodexo, which is a global multinational French headquartered company, for about 18 years. I lead global diversity, equity and inclusion, corporate responsibility, and wellness for the organization. At the time, the organization was in 85 countries with 465,000 employees. So, a complex, very geographically dispersed organization.

I lead their culture change and their DEI transformation efforts. I decided to rewire in January of 2020. And just a couple of months before COVID hit, I used the time, the COVID time, to really hunker down and write my book. For me, this book was sort of an act of closure. It was an act of legacy. It was my way of giving back what I had learned to others who do the sort of very difficult, challenging work, the heavy lifting, so I wanted to share the mistakes I had made in a very sort of authentic, transparent way, so others don’t fall into the same missteps and make the same mistakes.

And so today, I do several talks, podcasts like yours, and other book talks. I also engage with executives. So, I do strategic coaching with executives and chief diversity officers. The third bucket that I play in is my board work, which I absolutely love.

I’m on the board of several nonprofits, a couple of diversity advisory boards for corporations like Sanofi and for Charter Communications, and several nonprofit organizations, including Tent Partnership for Refugees, that focuses on the empowerment of refugees globally. It’s funded by the CEO of Chobani Yogurt, Hamdi Ulukaya, who’s just an amazing human being.

I also am on the board of Galt Foundation, which places people with disabilities, one of Gates Foundation’s initiatives WomenLift Health, etc. So, several nonprofit boards. Those are sort of the three buckets that I play. Book talks, strategic advising and coaching, and then my board work.

MELINDA: Amazing. I also was writing during the pandemic. I know that was, in many ways, very difficult for me. It’s such a tough time to be writing a book, but important, obviously. And so, let’s talk about your book more. Your book is organized into five Global Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Principles. Can you share those with us?

ROHINI: Yeah, sure. Do you know what I found, Melinda? Given the sort of complex and dynamic nature of this work, global work, there’s really no playbook, there’s no checklist. And honestly, best practices are far from adequate. But each time I did this work in different parts of the world, I found the sort of five core principles or five key elements that drive success.

What I found was that these principles provide a throughline to global DEI work. Each principle is a very simple statement that includes my experiences, that includes anecdotes, and the successes of my colleagues. They’re simple, but they’re very disruptive. They’re not designed to provide standards of plug-and-play templates based on what’s worked in the US.

In fact, to be honest, Melinda, that’s been one of the foundational mistakes in global work is to replicate what’s worked in one part of the world and in another part of the world. They can be applied with sensitivity to any culture. It really empowers leaders to develop their own solutions and not mimic any one country or leader’s experience.

The five principles. The first one is “make it local.” And what this sort of refers to is that global change really needs to be anchored in an understanding of the local context. It has to be rooted in local particulars. It has to be informed by the history, the culture, the language, and the laws in each place.

I think one of the key pieces here is also to sort of consider how identity is defined, how it’s expressed, and the power structures and identify dominant and subordinate groups because they differ. But understanding that context is only the first step because the first step in finding strategies to advance underrepresented groups locally doesn’t mean accepting the status quo because outside influence can be a catalyst for change.

They can raise issues that people within a culture cannot. But it’s best when they’re sort of partner with local change agents to find the right entry points and ensure relevance. So, it’s about understanding the context but pushing for change.

The second is “leaders change to lead change.” We all know that inclusive leadership at the senior level is absolutely fundamental to ensuring that DEI is sustained. And honestly, when leaders really lead with authentic purpose and passion, the organization can go from this performative action to really sustainable progress. But to do that, leaders have to internalize the benefit of DEI to themselves and to the organization. And oftentimes, it takes a disruption of their worldview.

Ultimately, I think that leaders have to lead DEI as they would any other business imperative. They have to be transformative, inclusive leaders that combine sort of these inclusive mindsets and behaviors with concrete action because personal behavior demonstrates a conviction, but it’s really taking the action that signals a commitment. So, that’s the second.

The third is “it’s good business too,” the third principle, which simply states that without a compelling rationale or reason for the change, 70% of change efforts will fail. But DEI cannot be siloed or bolted on in an organization. It has to be congruent with the organization’s purpose, the mission, how business is done, et cetera.

The fourth principle is what I call “go deep, wide, and inside out.” Organizations are comprised of these interconnected systems and work in concert with each other. DEI really needs to be infused into all of the processes, policies, and structures internally. So, you have to take a systems approach, as well as the external ecosystem.

Lastly, the fifth principle, the fifth throughline, is to “know what matters and count it.” This is simply about having the right metrics because they form the sort of global framework in a cohesive narrative, and they can spotlight problem areas, but they can also be instruments for change, but they have to be aligned with the local context, and you have to hold the teams accountable.

So, those are the five principles. Make it local; leaders change to lead change; it’s good business too; go deep, wide, and inside out; and know what matters and count it.

MELINDA: Fantastic. You hinted at this already. Often in our global diversity, equity, and inclusion work, we hear leaders outside of the US say, “Well, we don’t have issues with diversity and inclusion here. It’s different here than in the US.” There’s a perception that diversity, equity, and inclusion is a US concept. Of course, you and I know that every region has work to do around diversity, equity, and inclusion. How do you respond when people say this?

ROHINI: Yeah. I think there are a couple of things here that are really important because you’re right. I think that outside the US, we hear this pretty often that this is not relevant here. This is very much of a US thing. This is a US fad. I think what we have to do is to really sort of look at it from there, look at the situation from their perspective, right.

If we approach a situation thinking that race and racism, for example, are going to show up the same way as it does in the United States, we’re going to miss some really important nuances. So, we really have to look at who the dominant and subordinate groups are within that particular context. It may be based on caste. It may be based on ethnicity. It may be based on religion.

With that understanding, we also have to be very aware of the sensitivities and the politics surrounding dominant and subordinate groups because these are very highly charged situations. So, I think that’s sort of the first step is sort of understanding.

I think the second piece is to really sort of translating it in terms of business terms, particularly when you’re talking about a corporation. So, you know, make it about their business. When you’re talking about a subordinate group, and if that subordinate group is a religious minority or an ethnic minority, translating that into, you know, these are your customers, right?

If it’s about a food chain or restaurant chain, these are your customers who are going to be eating at your restaurant. You really need to be paying attention to how you are both serving this customer base but also how you include this customer base in your workforce because, ultimately, it’s about business. It’s about being successful. If you are not sensitive to providing culturally competent customer service for this particular marginalized group, you may be missing out on a whole segment of a customer population. So, make it about their business.

I think the other piece is also building relationships, right? So, working with local allies who can speak on your behalf because understanding who the power brokers are, convincing those power brokers, or allowing them to basically speak, empowering them to speak on your behalf to carry the messages forward for you, I think is very important.

I’ve also found that showing them what their competitors are doing and what their peers are doing from other companies is really an effective strategy as well. Either local companies or even those from outside of their particular geography because I think that we talk about the sense of belonging, and we talk about in terms of belonging to an organization, so it’s part of an inclusive culture.

There’s another aspect of belonging, and that is the need for an organization to belong to these sort of diverse elite organizations or organizations with a sense of cachet and credibility. Everyone wants to emulate those organizations, so bringing that to them so that they want to emulate an organization that’s actually addressing diversity, equity, and inclusion, bringing the CEOs of those organizations, and introducing them to some of those organizations is really critical.

I think it’s also important to use sort of an outsider status to ask questions that insiders cannot because sometimes it’s so politically charged, right? So, if it is an ethnic or religious minority that it’s politically charged to have those conversations within a context, as an outsider, I can go into that situation and ask the question and start the thinking process.

So, I think there are several ways of doing this. There’s no one sort of pat answer. But I think ultimately, what I call head strategies or the cognitive strategy is going well so far, and it has to really be combined with putting somebody else in the shoes of those that are marginalized, giving them lived experiences of those that have been discriminated against and marginalized. I think that helps to create that sense of empathy and create that connection with the individuals.

But I will say that when one does that, my experience has been oftentimes, it’s through sort of storytelling, right? Whether it is addressing issues of LGBTQ in countries that have not addressed these issues. Or LGBTQ+. Not necessarily LGBTQ+ friendly. Oftentimes, it’s lived experiences and maybe from within or maybe from outside the culture that creates this sort of awareness and empathy. But what it does is it puts the burden on the person who’s sharing their lived experience.

So, I think that one has to be very careful about how we get people to share their lived experiences and also maximize that opportunity. I think leaders need to take responsibility for their own learning. So, the burden is just not on the individual with the lived experience.

I think there are many different ways of addressing this. But ultimately, I think it’s about understanding the context. It’s about building the relationship, having allies to carry your messages, and also really making it sort of part of the business narrative.

So, I hope that answers your question.

MELINDA: Yeah, absolutely. Maybe you could share some examples of that learning around what leaders can do to learn, unlearn sometimes, and relearn, right, and really disrupt the worldview that they might have to emerge as more inclusive and transformative leaders.

ROHINI: Yeah. So, there are a couple of stories that I’d love to share. This one particular leader was in Europe, and he mentored a woman from a different country. He mentored/sponsored her. She was actually managing high-security prisons at the time.

And so, after mentoring her, a couple of months into that particular relationship, he came to me, and he said, “You know, if you had presented me with two candidates, a male and a female, and asked me to select the most qualified candidate for high-security prison, I would have chosen the man hands down, because you need an aggressive and assertive style. Women typically do not have that.”

He said, “But after mentoring her,” this individual, this leader who was managing the prisons, he said that she has a very different leadership style. She is collaborative. She does not have an aggressive leadership style, but she’s extremely, extremely effective. So, this was his learn-unlearn-relearn process. And also sort of disrupted his worldview and the biases that he had.

He concluded by saying, “Tomorrow, if I was to be in a recruiting process and you presented me with two candidates for any job, I will not let my unconscious bias come into play because this has been real learning for me that I have this notion of a leadership style that’s effective. That’s just been busted because I can see that she has a different leadership style, and we need to be open to different leadership styles, but she’s extremely, extremely effective.”

So, that would be one. Can I share another?

MELINDA: Yeah, absolutely. That was fantastic.

ROHINI: This other one has to do with a leader from Europe. I had shared with him all of the data, the business case, and all of those things, but he was not buying. I knew that he wanted to belong to the sort of diverse elite companies and CEOs and network with them.

So, I introduced him to a cross-company mentoring program. He mentored this woman from a different company. They’ve developed a very trusting relationship with each other. She got laid off from this other company. Through that process, she obviously sought his support. She shared with him what she had gone through being the only woman on the C-suite, being marginalized, being talked over, all of these things.

He came to me and said, “I cannot believe that women have these experiences even at such a senior level in organizations.” And this was like a real wake-up aha-moment for him. It’s not that he hadn’t heard these things before. And he said, you know, if you had told me that a woman in my organization was being laid off, I would have said, well, those are the breaks in the game, and it happens. It can happen to anyone.

But after mentoring her and listening to her experiences, he said, this is absolutely unfair. It should not happen to anyone. It should not happen to women. He then went on and said, “I want all of my 12 direct reports to sponsor a woman from the organization and sort of having this learn-unlearn-relearn sort of process, so they can also be open to different experiences.

I think those kinds of things. I think this whole notion of sharing lived experiences is very, very important, Melinda. One other quick story. The CEO and I actually include this in the book, in my book, Leading Global Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, where I talk about one of the previous CEOs of Sodexo. We were focused on a global gender strategy.

I remember a conversation with him when he said, “You know, we’re focused on gender. Why are you diluting the focus by talking about things, issues of race and racism? They’re not relevant in France and in Europe.” He’s right. They show up in a different way. So, the way we look at it in the US is not necessarily relevant.

I realized that I needed to sort of expose him to a learning opportunity to expand his worldview. I invited him to the employee resource group meeting in Texas. He cleared his calendar. He came for a day and a half. He attended the sessions. It was his experience of being one of the only White men in the room, one of the only French men in the room. He is a French CEO, combined with listening to the lived experiences of the Black men and women in that room, that was very transformative for him and really did disrupt his worldview to a point where when George Floyd was murdered, he sent us a really heartfelt message to the organization, something I don’t think he would have done had he not had that particular experience.

So, I think these are sort of some examples of the sort of disruption of a worldview which really takes not necessarily the cognitive, but sort of experiences and exposure. So, the heart strategies.

MELINDA: Yeah. It sounds like also, each of those leaders… one is exposure, right, and making sure that you’re building ways to build those connections and understanding about each other and that openness too. You have to have that openness to change. Right?

ROHINI: Absolutely, right. Yeah. Absolutely.

MELINDA: Can you share some examples of missteps that leaders have made when taking their program global?

ROHINI: So, missteps, there are plenty, plenty, but maybe I’ll just start with my own misstep, Melinda, if that’s okay with you. So, I was working for Sodexo in the US initially and then took on the global role. I went back to India to do D & I work in India.

Now, I knew the language. I had grown up in India. I felt like I understood the culture. So, I’m sitting in this room full of entry to mid-level women managers, and you know, sort of started talking to them about mentoring and sponsorship and leadership development in terms of advancing their careers.

I just was like, blank stares. I was not connecting. So, I tried a few words in Hindi but still got nowhere. And then I took a deep breath. I stepped back and said, “Can you share with me how the company can help you with your career and your career experience at Sodexo?”

After a minute’s silence, one of the women raised her hand and said, “We live in these multi-generational joint families. I cannot stay late for work. I can’t take on any additional assignments. I can’t take on any training because I have to go home and I have to cook for my family. I have to take care of the house. I have to do all this housework. And my mother-in-law basically is waiting for me to come and cook the dinner and gets really annoyed if I’m late, et cetera.”

It was really an aha moment for me, Melinda, because I had completely forgotten this joint family multi-generational dynamic. I had forgotten the role of the Indian woman as a mother, a wife, and also as a daughter-in-law. And honestly, I’d forgotten my own limitations as a multi-dimensional being. I focused on this one aspect of my shared identity with these women and overlooked the many other differences.

So, the misstep really was an early lesson for me that it’s not useful to export initiatives that have worked in one part of the world. And also that I need to check my own presumptions. And then, sort of fast forward, I think it was around the same time. I did this work in France. I’d started this work in France. So, I had sort of learned through that experience as well, not to assess situations sort of with this one-dimensional worldview.

I had organized a meeting in Paris, and this was just with women, and the CEO had personally invited them. We wanted to assess what the culture was for women. It was a half-day session. He invited them. Many of the women in Europe were very critical of the meeting. They felt that they had managed to overcome the barriers to career advancement, and therefore there was really no need for a special session focused on the challenges that women encounter.

They really didn’t want to be part of this meeting comprised only of women. They said, “We only participated because the invitation came from the CEO.” Many of them were in their positions not because they were women but because they had earned that job. So, I was actually quite surprised and, frankly, caught off guard by this resistance to a women-only body of meeting because it was perfectly acceptable in the US context at that time.

So, to me again, this misstep was, you know, assessing the situation with this sort of one-dimensional worldview. I should not have assumed that the women-only body would have been embraced everywhere in the world. So, a couple of missteps on my part, as an example.

MELINDA: Yeah. May I ask, what would you do differently now in that situation?

ROHINI: Yeah. So, I think, what would I do differently in that particular situation? I think going in without these preconceived notions about what’s worked in the US and my desire and enthusiasm to replicate what’s worked in the US because it’s going to work everywhere else in the world. That really is one of the issues.

We often approach the work with our own limiting worldviews, right? We come with this set of experiences. That’s very antithetical to the outcome that we’re seeking. So, I really have to start. I would have started with them and where they are. Understand that, get their perspective, and then be a catalyst for change.

So, it’s not just about understanding the local context, but it’s also pushing for change because it is important to push for change. I had to do it starting with the local context and then bring my outsider perspective versus taking an outsider perspective in and then expecting things to evolve the way I’d been used to them evolving.

MELINDA: Yeah, the first principle of your book is around making it local. What are some practical ways that people can think about doing that? What are some practical things we can do to localize that work?

ROHINI: I think sort of examples and stories, perhaps, are the most useful, Melinda. So, I’ve said a couple of times that making it local doesn’t mean accepting the inequities. Let me just share a quick example from Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Arabia ranks, even today, 146 out of 153 countries in the World Economic Forum’s 2020 Global Gender Gap Report. So, I think it hovers around the same. And for years, Saudi women were really considered sort of legal minors. They had to have male guardians to travel and work.

One of the leaders that was country head in Saudi Arabia noticed things opening up. He was an expat leader, and he headed up the business there. He decided as things were opening up, to hire more women, Saudi women. There was really no dearth of qualified women because Saudi women have a very high education level.

In 2015 or so, they had a literacy rate of 91%. Many of them were very eager to advance their careers. But according to Sharia law, they had to work in a separate room with the door closed. They had to have an intercom. They were not to be seen by male colleagues, and they had to communicate through this intercom. Men couldn’t enter the space that they were working in without announcing themselves. And if women were to go out to a meeting, they needed a male chaperone.

Now, viewed through a Western feminist lens, these working conditions would have been absolutely unacceptable, right. And anybody, you know, a sort of leader coming in might be tempted to insist that the women integrate fully in the workplace. But if you have that sort of a situation and ultimatum, it would have been counterproductive because women would not have joined this particular workplace. You wouldn’t be able to hire them.

So, what this particular leader did was he realized that women, in order to advance in their careers, would need to occasionally meet with male colleagues. But the conservative men pushed back because they felt it was unacceptable without a Saudi or Muslim man to accompany them.

What this leader did was he put the dilemma back on them by saying, “Okay, you can accompany them to every single meeting that they have, or you find a solution.” These conservative men then came up with a solution. They said the women could meet with the men as long as they were sitting at different sides of the table and the door was open.

In terms of practical sort of tips, what he did was disrupt the status quo, but he did it within the local context. He had whatever the setup was by Sharia law for the women to work in the workplace. But you know, as an outsider, he had the freedom to push for increased hiring of women. And then, what he did was he invited the local change agents. He invited the insiders, those with the local knowledge, and even those who were most resistant to kind of propose changes to women’s opportunities.

So, it’s a question of, again, as I said before, understanding the context, right? Working within that context, using outside of status. This was not something that he felt comfortable with, but he had to sort of accept using that understanding and then gently nudging and pushing for change in order to disrupt the status quo, but doing it with local allies, doing it in partnership with those who knew how to pace the changes, what the right entry points were, etc.

MELINDA: Yeah, that’s fantastic. Super helpful. I will say that multinational clients, in general, have a tough time sometimes addressing LGBTQIA+ rights and inclusion across global regions. I know many companies are working to navigate this. Can you share an example of how you’ve seen companies really support LGBTQI+ employees in regions where it might be unsafe to even be out?

ROHINI: Right. You’re right. I mean, the sad truth is that laws in over 70 countries criminalize same-sex couples. But you know, I really believe that that does not mean the change agent simply sort of accepts the situation. We’ve got to be able to push and disrupt the status quo. It’s about the safety and well-being of our own employees in those countries as well, right?

So, it doesn’t mean backing away from sort of these difficult challenges. And let me just share a quick example of that. Along with many companies like Google and Barclays, and several other multinationals, they sponsored Singapore’s Pink Dot festival, celebrating the LGBTQ community.

And as you know, Singapore is not a gay-friendly country. So, these sort of outsider companies uses their influence and their money to support local insider change agents, local companies, who are trying to carve out a safe space within their country. It was a way of validating their own employees in Singapore, but also the broader LGBTQ community in the country, in the local companies, etc.

Now, in 2017, the Singaporean government clamped down and banned foreign organizations from sponsoring this Pink Dot festival. But what had happened was that enough momentum had built up so that over a hundred local companies came together and were able to keep that sort of going.

I think companies can take a stand (A) for their own employees in terms of policies and safety. I think their own values and policies trump those of the country because that’s what is most important while you’re working at a particular company. It’s the company values that provide safety for all employees, including the LGBTQ+ employee. So, I think that’s one.

The second is I think they can even do more by sort of nudging and pushing. And this is a great example of how these multinational companies did nudge and push beyond just their own workplace.

MELINDA: Yeah, absolutely. Holding true to your values. And then pushing for change. Maybe the third is really doing all that you can internally to support and create a sense of belonging.

ROHINI: Absolutely. Yeah.

MELINDA: Yeah. You’ve addressed this a little bit here and there. How can we address issues of race and racism, race, ethnicity, and racism locally without imposing that US framework?

ROHINI: Oh, my goodness, Melinda. That’s been the most difficult. Honestly, it’s been the most challenging. I might just muddle through this answer, but race is definitely the most challenging to address globally. And to be honest, as I wrote the book, my regret there was that I didn’t address race more substantively globally because it is so difficult.

But when I talked to people, to my peers, I realized that there were very few best practices. Very few people had done much in this area. It’s extremely sensitive. It’s politically charged. It’s talked about in court or not talked about at all, particularly in Europe.

Now in Europe, we chipped away through the refugee employment program, where we provided jobs and expanded empathy at work. This was a good entry point to the discussion on race because refugees frequently are from visible, non-dominant groups.

What’s interesting, Melinda, is that more recently, you know, companies who saw this refugee employment program have nothing to do with DEI and have nothing to do with race. More recently, as I’ve talked to them, I’ve realized it’s opened their eyes because they’ve seen how Ukrainian refugees have been treated and embraced in a very positive way. Because racially, there is more of a sense of identification with the Ukrainian refugees than with the refugees from Syria or Afghanistan, or from Northern Africa. So, I think this has opened up this conversation about race and racism.

I’m proud of that work, but I mean, I regret that we didn’t make more headway. But as I said, I wasn’t alone. What’s challenging is that racism is both universal and highly, highly specific. Every context has its own dominant and subordinate groups. And these differ.

Race and racism are fluid, and it’s really shaped by a country’s history and culture. So, you can’t use this cookie cutter approach because oftentimes, it’s tangled up with other identities like ethnicity, religion, and caste that take more prominence thanrace.

In the United States, race is clearly the driving social force. But elsewhere, the race is just one of those several identities that divide and may play a much less prominent role. So, if we expect racism to be sort of expressed in a manner in which we are familiar, we’re going to miss those important entry points like the discrimination against the lowest caste or religious minorities in India or the ethnic undertones and politics in Kenya.

In some parts of the world, it may not be appropriate to approach the topic through the lens of race, but more through like decolonization, for example, in AIPAC. So, you have to look at this intersectionality. As I said, to complicate things, it’s a very highly emotive and politically charged topic.

So, in France, because I work for a French company, you’re forbidden to gather data on race or ethnicity, and race was removed from the Constitution in 2018. This was in response to the persecution of the Jewish people in an effort to build/rebuild France after World War II as indivisible, which meant that they didn’t want to identify people by community affiliation but rather by objective criteria, like migration and citizenship, so that the state couldn’t use identity data for state action.

All these things make it very sort of complex. We have an opening now. Post the murder of George Floyd and the video going viral there were protests all over the world. It’s opened up a space that was previously closed, and we need to enter that space aggressively and really address issues of race and racism, but from a very local context, because how it shows up, these dominant and subordinate groups, is very, very different.

MELINDA: Also, one of the things that I’m finding in our work is individuals who struggle to be good allies across global teams, people working globally with individuals from around the world. There are certainly cultural barriers. I’m not sure barriers are the right word, but cultural differences. And also, just the lack of understanding of each other, I think too. What does global allyship look like? Can you give an example or two where you’ve seen good allyship in action across global teams?

ROHINI: Yeah. So, there’s one great example that I’d like to share. At Sodexo, we had this sort of group called SoTogether, which was sort of an internal gender advisory group comprised of men and women. This particular group really sort of exemplified global allyship in action.

What we would do is we’d meet in different countries. Sometimes it would be a country where there were some really good best practices that they wanted to showcase. We’d have a two-day meeting. Very, very wonderful agenda with speakers, a client event, a meeting with the local women, etc.

Sometimes it will be in a country where they really had done nothing and needed to move along. So, this particular group really brought a sort of allyship to those different environments. One example that I have was when we met in Germany, we had the sort of senior leadership team. There were seven men, all over six feet, all in identical blue suits, white shirts, and ties.

They had never even thought about D&I. And here, they were being put on the spot because this group said, “We want to hear what you’re doing in Germany for diversity, equity, and inclusion. So, they sort of had to scramble and basically put something together. You could see that discomfort.

This particular group, SoTogether, the Women’s Advisory Group that we had, really supported them in helping them to move and to really get started on this journey, also supported the women, so worked with the women to really mentor them and support their career advancement. And fast forward, you know, the German country head then ended up being a woman. She had a very, very diverse team.

So, I think this sort of piece around global allyship in action, I think what’s wonderful is allies from across borders can bring cross-border ideas and information and perspectives that help to ignite change within a particular context. They can be allies and support that particular team within a country to really move forward by bringing in this sort of outside ideas and perspectives.

I think that’s one example. I think the other one would be in talent reviews. Listening in on discussions and having leaders basically challenge some of the unconscious biases. I think allies can challenge unconscious bias. When someone says, “Well, she can’t move because she has little children.” Or, you know, “Have you asked her if she wants to move?” I’ve heard allies basically challenging those unconscious biases. I think that’s another very effective way of being sort of global allyship, if you will. So, let me just stop there.

MELINDA: Yeah, that’s fantastic. Thank you for leaving this legacy and the resources for everyone to learn and do better when it comes to global diversity, equity, and inclusion programming and leadership. What do you see as the future of diversity, equity, and inclusion? What’s the moment calling for now?

ROHINI: I think despite the best-laid efforts, Melinda, organizations are flailing to sustain DEI. I think they often have these sorts of performative statements that are made. They have money being put behind DEI. You have sort of diverse professionals appointed. Many of them are figureheads with no real positioning of power.

I think that to ensure that the sort of actions aren’t just performative, you really need to disrupt the status quo. That needs to become sort of a normalized part of our conversations because giving money and adding the acquisitions is easy and can feel like enough, but it really is not.

The other piece is often that, you know, competing business priorities become a convenient excuse to dilute the focus on D & I. We saw that, right? Because when people see this sort of incremental initiatives that are dispensable during crisis over the economic downturn and COVID, D & I budgets were downsized, and then teams had to deal with the disparate impact of the pandemic on women and marginalized communities, and also the systemic racism further sort of magnified with the murder of George Floyd.

I think we can do things at the individual level. I think, first of all, we have to look at new ways of understanding identity. Given the intersectionality of identities, I think we can all be allies because, ultimately, transformation happens at the intersection of the personal and the systemic, and its work that’s ongoing. So, it really has to be a personal and professional journey for each of us. We can all be allies.

At the organizational level, I think we have to work hard to eliminate those harmful practices and have supported some people’s success. And what makes these sorts of practices oppressive and tenacious is that leaders don’t even acknowledge what got them into their positions. And then, I think organizations are linked to this broader society, and stakeholders are calling on organizations to take a daring and unequivocal stance on injustice in their communities. So, they need to take those stands.

I think the moment is calling for each of us to be allies. The moment is calling for organizations to audaciously eliminate these harmful practices. And the moment is calling for organizations to take a daring unequivocal stance on injustice in the communities.

MELINDA: Absolutely, 100% agree. It’s so important, too, as we go into the next era in our economy as well, where, as we know, it’s really important to keep the budgets strong around diversity, equity, and inclusion despite the economic downturns. Those are often the quickest budgets to be taken away. And that just is going to erase a lot of work and push yourself backward.

So that and all of what you said is so important right now, at this moment, for many, many reasons. Thank you, Rohini, so much. And obviously, there’s so much more in your book. So, I encourage everybody to read it. Where can people learn more about you and your work?

ROHINI: Thank you. So yeah, my book, Leading Global Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, is available on Amazon and all the local bookstores, Barnes & Nobles, etc. You can also find out more on my website at www.RohiniAnand.com. So, thank you, Melinda. This was a great conversation. Thanks.

MELINDA: Absolutely. Absolutely. My pleasure. Thank you to our interpreters, and thank you all for listening or watching and, most importantly, taking action.

MELINDA: To learn more about this episode’s topic, visit ally.cc.

Allyship is a journey. It’s a journey of self-exploration, learning, unlearning, healing, and taking consistent action. The more we take action, the more we grow as leaders and transform our communities. So, what action will you take today? Please share your actions and learning with us by emailing podcast@ChangeCatalyst.co or on social media because we’d love to hear from you.

Thank you for listening. Please subscribe to the podcast and the YouTube channel and share this. Let’s keep building allies around the world.

Leading With Empathy & Allyship is an original show by Change Catalyst, where we build inclusive innovation through training, consulting, and events. Appreciate you listening to our show and taking action as an ally. See you next week.