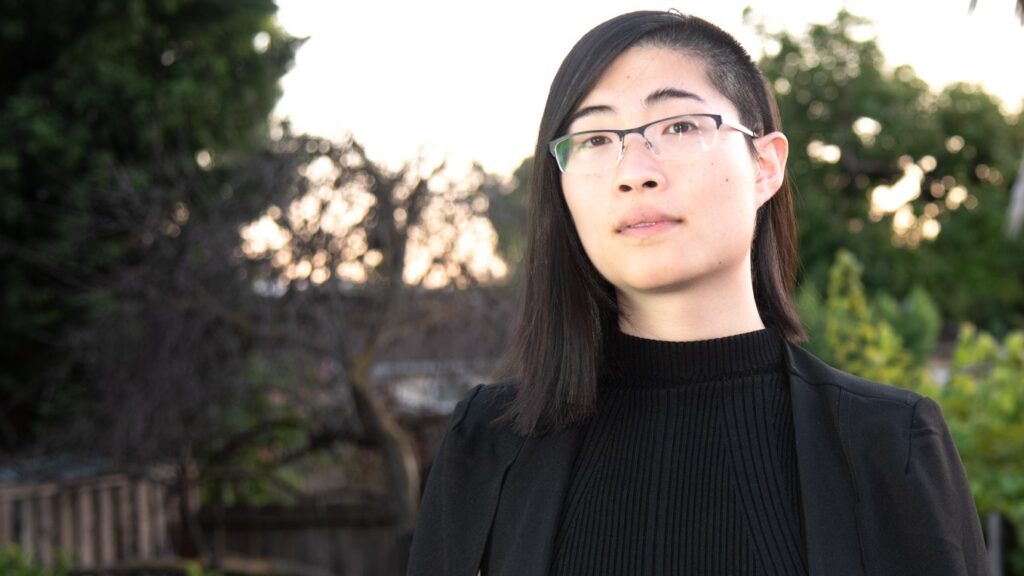

Lily Zheng (they/them) is a sought-after Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion speaker, strategist, and organizational consultant who specializes in hands-on systemic change to turn positive intentions into positive outcomes for workplaces and everyone in them. A dedicated change-maker and advocate named a Forbes D&I Trailblazer, 2021 DEI Influencer, and LinkedIn Top Voice on Racial Equity, Lily’s work has been featured in the Harvard Business Review, New York Times, and NPR. Their most recent book, DEI Deconstructed, centers on accountable and effective practices to achieve DEI outcomes in organizations.

Finding Your Power To Create Systemic Change With Lily Zheng

In Episode 105, Lily Zheng, Consultant at Zheng Consulting, joins Melinda in a discussion on how we can use our power to create real systemic change around diversity, equity, and inclusion. They explore different types of power and practical ways we can build movements that address inequities in the workplace. They also discuss the importance of trust in creating change and how managers can earn their team members’ trust by understanding and utilizing the currency of trust when making decisions.

Additional Resources

- Learn more about Lily’s work at Zheng Consulting

- Read Lily’s book, DEI Deconstructed: Your No-Nonsense Guide to Doing the Work and Doing It Right

- Check out the full list of Lily’s books

- Read the book, Diversity, Inc.: The Fight for Racial Equality in the Workplace by Pamela Newkirk

- Read the article, “French and Raven’s Five Forms of Power: Understanding Where Power Comes From in the Workplace”

- Read Melinda’s book, How to Be an Ally (McGraw-Hill)

- Download the “The State of Allyship Report: The Key to Workplace Inclusion”

- Watch or listen to EP99: “Building Psychological Safety And Trust On Teams With Amy Edmondson”

- Watch or listen to EP76: “Psychological Safety & The Neuroscience Of Trust With Dr. Vivienne Ming”

This videocast is made accessible thanks to Interpreter-Now. Learn more about our show sponsor Interpreter-Now at www.interpreter-now.com.

Watch Episode

Subscribe To The Show

Don’t miss an episode! Subscribe on your fav app to catch our weekly episodes.

Accessibility: The show is available on YouTube with captions and ASL interpretation. Transcripts of each episode are available by clicking on the episode titles below.

Subscribe to our Podcast newsletter

When I help people understand how to use power as an individual, I have to help them understand that it’s not just about getting [promoted] to manager and then finally you can do something…. There’s an infinite number of things you can do to build, to gain, to use power, to make change as an individual. It just depends on, where are you based in the organization? What role do you have? What access to networks do you have? What communities are you close to? What can you do to use your own positionality to enact the sort of change that you want?

Learn more about the host and creator of Leading With Empathy & Allyship, Melinda Briana Epler.

Browse Our Episodes by Category

Recent Episodes

Transcript

MELINDA: Hello, everyone. I’m Melinda Briana Epler, Founder and CEO of Change Catalyst and author of How to Be an Ally. I’m your host of Leading With Empathy & AllyShip. Welcome!

Allyship is about learning showing empathy and taking action. That process often includes learning, unlearning, and relearning, then building empathy for people with different experiences, and above all, taking consistent action. So each week, we’ll learn from somebody new. Please be open to new ways of thinking and understanding. You can learn more about my work and sign up to join us for a live recording at ally.cc.

Let’s get started.

Hello, everyone. Welcome. As you all know, I’m Melinda Briana Epler, the host of Leading With Empathy & AllyShip. So I wanted to let you all know that I am recovering from COVID today, my voice may sound a little bit different. For many of us, COVID is more than a cold, more than a mild cold. So when we want to go back to normal, please keep that in mind. This is a new normal. Please be kind to yourself if you’re recovering, be kind to those around you for those who are recovering. I encourage us all to redefine normal, to protect yourself, to protect the people around you from getting sick. Because you never know what their immune system is like. Some folks are disproportionately impacted by this disease, due to disability, due to age, income, access to quality healthcare, job, whatever their job type is, gender, race, ethnicity, and more. So it’s not always a mild cold. For me, it’s been much deeper and much longer. So practice physical distancing, masking, boosting, and staying home if you’re sick, please.

All right, so I want to jump in and talk about our guest today. Our guest is Lily Zheng, consultant at Zen consulting and author of the new book DEI Deconstructed: Your No-Nonsense Guide to Doing the Work and Doing It Right. We’ll be talking about how you create real systemic change around diversity, equity, and inclusion. We’ll discuss some key learnings from past DEI work, the role of trust in power dynamics, and the ways that we can use our power to create lasting change. If you all have read my book, you know that this is the step on leading the change; the ways that we can all lead the change to create diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces.

So welcome, Lily. It’s great to have you here.

LILY: Yeah, thank you so much for having me. I’m excited to be having this conversation today.

MELINDA: Awesome, likewise! So, Lily, would you start by telling us a bit about you, your story, and how you came to do the work you do, and maybe start with where did you grow up?

LILY: Sure. Well, there’s a lot to talk about there, so I’ll try to keep it brief. But I grew up in the San Francisco Bay area on the peninsula in a relatively small town. I think we’ll have to fast-forward a decade or two if we want to talk about how I got into this work. So I’ll go ahead and do that. I think things really started when I was in college and engaged in student activism. This was really around a time when the national conversation on racial injustice was very much just beginning. When I was in college, I was learning, as a lot of students do, about the history of this country and about the many inequities in the world around us. I think I had had some experience before that point, growing up. Chinese-American, coming out as a trans person in high school, I definitely had experiences with trying to navigate systems that weren’t built for me and laws that didn’t exist, but now do. Protecting, for example, my right to use bathrooms corresponding with my gender. So I certainly had lived experience as a multiple marginalized person.

I think where the work really started, though, is as a student activist, I spent a lot of time trying to change my university. There were a lot of student activists in college. Like, many folks saw policies that weren’t working, I saw my classmates having experiences that were really negative with professors, I saw the lack of faculty diversity, I saw disabled students and trans students and Muslim students not getting the support they needed, and so on and so forth.

So as an activist, I was really trying to change the university that I was in. But I realized that I and many other people around me had no idea how I was going to go about doing that. Universities are big organisms; they’re giant machines. They outlive the four-year timespan that undergraduate students spend in them. So I was really learning the hard way that when you butt up against a system that’s existed for far longer than you have, things don’t change on a dime. Like, things don’t change just because you’re frustrated at things, or you staged one protest, or you deliver a social media smackdown on one professor you don’t like. I’m happy to talk more about it later, I suppose.

But the big moment for me was engaging in direct action as a student, I was arrested while blocking a major bridge in the Bay Area. The intention behind that direct action was, we draw attention to racial injustice, we raise the visibility of our solidarity movements, we connect all these disparate issues; we finally force the university to recognize how important it was to take these issues seriously, all very inspirational stuff. And what followed was six months to a year of trauma and therapy and going through the “justice system,” and genuine disempowerment. I’ll say trauma again, because it was genuinely traumatic for everyone involved. And at the end of the day, when we looked at the university we were trying to change, we couldn’t say that our action had done anything, which is one of the worst feelings for any activist, whether you’re a student or an activist in a corporation or a nonprofit or anywhere.

So that really pushed me to go back to the drawing board to really ask myself, how is it we change these giant machines, how is it we shift systems that changed my area of study? I got my master’s degree in sociology, focusing on organizational change, movement building, activism. I took all of that into the workplace, doing diversity, equity, and inclusion work right out the gate as my first job, right after college, doing this work firsthand, as a workshop facilitator, helping people build skills and change their organizations. But even that was, let’s say, not fully informed, not as informed as I could have been.

This will probably be an area of focus in our conversation today. But I’ll go ahead and preempt myself by saying, how I got to where I was today was because even doing DEI work, I started realizing that I wasn’t having the impact that I wanted to. I would go in and deliver these, in my opinion, incredible 90-minute workshops. People would be crying, they’d come to me afterwards, they’d say I really did something. But then if I had the luck to come back several months later, things hadn’t changed. If I followed up with the people who I talked to, they would tell me things like, well, I was inspired, and I really wanted to do something. But at the end of the day, things just went back to status quo.

I started realizing, so much of what I had learned about the DEI space, DEI work, changing hearts and minds, changing companies, wasn’t necessarily effective. That started the long journey to get to where I am now as a practitioner that, I think, has a very different approach to this industry and this work. It’s why I wrote my book, DEI Deconstructed, to really find ways to democratize access to change making tools for everyone. To really write the book that I wish I had, as an activist, as an early practitioner, even now, to guide this really difficult work, to make sure that we’re not just talking the talk, to make sure we’re not just putting in our good faith efforts to do change. But we can actually hold ourselves accountable, we can actually achieve diversity as an outcome, we can achieve equity as an outcome, inclusion as an outcome.

So that’s the short version. But covered a lot of ground there, and I’m happy to talk more about it in a bit if you’re curious.

MELINDA: Thank you for sharing your story. One of the things that struck me when reading your book was, after you talk through some ways that diversity, equity, and inclusion has not worked, and what things that you have learned in doing your work and things that you’ve learned in seeing the industry over time, one of the things that you wrote is, “You might be wondering, Lily, if you’re so frustrated with all of this, why the hell are you in this industry at all?” I think that is something that a lot of diversity, equity, and inclusion advocates and practitioners have asked themselves from time to time. So why do you do this work?

LILY: Yeah, that’s such a good question. I think I do this work because I have hope for it. It’s not just the sort of aspirational, empty hope that comes from, well, things should get better in the future because they have to. But rather, a hope that comes from efficacy. We know at this point, we have a lot of knowledge, a lot of understanding, a lot of research on what actually works. The reason why I wrote a book about what works, and not just a book about how horrible and broken the industry is. By the way, there are several books like that, and I would invite you read them. Diversity, Inc. is one of the best ones, a really, really interesting, fascinating book. But in my opinion, really cynical, not a great book to read if you’re looking for hope. But very critical, and I think it’s on the dot. But those books exist. I wrote a book that merges the practicality of cynicism, with the forward-thinking, like hope that comes in a lot of aspirational DEI books.

Right now, in this space, we tend to have this binary of books, of either these super cynical books that are like, DEI is broken, it’s all doomed to fail, everything’s terrible, and the world’s going to end. And I don’t really like reading those books. Then we have books on the way other side that are just like, DEI is wonderful, it’s sunshine and rainbows, we’ve just got to keep on hoping and cross our fingers, hope that people will see the light and change their own hearts and minds and end racism by the goodness of their hearts. No, I don’t believe in that either. If that worked, we would have it already.

So I wrote my book to be something in the middle. I write several times in the book that being hopeful can’t just come from nothing, it needs to come from knowing what you’re hopeful for. And what I’m hopeful for is that practitioners can shift towards actual evidence-based practices, practitioners can hold each other accountable, organizations can have higher standards for themselves and for the third-parties that they reach out to to help do this work. It’s not just an aspirational thing for me, because I’m seeing it happen. I’m seeing organizations doing DEI correctly. Now I’m seeing many more of them do it wrong, and that’s disheartening and frustrating and makes me sad. But it’s clearly not all doom and gloom. Because those organizations that are led by extremely thoughtful people, that perceive DEI as a long-term organizational change project, that fund it, that resource it, that are deeply curious, that run experiments to see which interventions work, that are constantly trying to update their knowledge, that are bringing everyone along with them on the journey, that are working with the folks who are more or less bought in. Like, that stuff just works! It both works in the research, and it’s working in real life in these organizations. Yet, that model isn’t super-prevalent. Yet, we still feel a lot of snake oil, we still feel a lot of performative diversity.

So I want this book to shift more organizations and more practitioners in the direction of what we know to already be effective. It’s the fact that we have this understanding of what effective is that gives me hope in the first place, that’s why I’m still doing this work. If I thought the industry was beyond saving, we wouldn’t be here having this conversation today. I’d be talking about the next best thing once we’ve all gotten tired of DEI, and I’m not doing that. So I think we can do better.

MELINDA: Yeah, likewise. So can you share maybe the top two or three things that you have learned historically about diversity, equity, and inclusion work that informs your work today?

LILY: Yeah, so a few things. I think one is that you can’t succeed in DEI work unless you focus on outcomes. A big portion of the first half of the book focuses on input-centered DEI versus outcome-centered DEI. Input-centered DEI is defined by what we put in. So for example, I created a new policy, I deployed a new workshop, I brought in a speaker to give a talk. In the social science space, we call these things interventions; we call these our best efforts to shift systems. The thing is, with social science, you deploy the intervention, and then what you do? You collect data, you see if it worked, you identify if it had any unexpected side effects, you tweak, you redeploy, you try to get the result that you’re looking for. And that second half is completely missing from about 90% of DEI initiatives. There’s this sort of fire-and-forget mentality, where you just shoot off your initiative and you just say, well, that worked! Without looking to see if it worked, without tracking to see if it works, without collecting data, without asking people. Then, I don’t know, maybe 10 months later going: Hey, why are things exactly the same? That’s weird, let’s do it again. Let’s throw off the thing into the distance and see if it sticks. That’s just not an approach that works. The word I was going to say instead was asinine. It doesn’t work, I’ll say that, it just doesn’t work.

So if we want to actually do stuff that works, we need to realize: we have to define what works, we have to understand what end goal we’re getting to. And we need to measure things, we need to hold people accountable for achieving things. We need to be open to experimentation when the things we deploy aren’t working. We need to be open to accepting failure. We need to be resourcing the initiatives we’re doing to ensure that they work the way we want them to. We want to be developing things like a theory of change, a set of steps from Point A to Point B, that show exactly the causal mechanisms that cause our system, our organization, our company, to get from where we are now to exactly where we need to be. And these things are lacking, they’re just not there. So that’s the first big set of things, you need to be focused on outcomes.

The next is systems. Systems, systems, systems. You can’t change systems by trying to shift every single person within them individually. One metaphor used recently, not saying you should do this, because it’s probably very illegal, but the Tower of Pisa. The Leaning Tower of Pisa, it leans. It has an organizational slant; it has a bias. If you were to hypothetically fix the Leaning Tower of Pisa, would you take one brick at a time and try to build a new tower that goes straight up? Or would you try to shift the entire structure? You could probably feasibly do it both ways. But I guarantee you, if you tried to shift every brick one at a time, you’re going to be there for a long time. Moving one brick from a tower to the ground is a lot easier than fundamentally changing one person’s heart and mind. Yet, a lot of DEI work is focused on organizational transformation through individual transformation at scale, which when I started writing this book, I was pretty agnostic about.

My perspective was, look, if we can actually change organizations by doing a hearts and minds transformation of every single person within it, I will endorse this strategy. Yet, time after time after time after time, that doesn’t work. That’s been the approach that’s dominant in our industry for three, four, or five decades. And where are we? We haven’t made change. This hearts and minds approach, I think, can be effective. But I don’t think it can be effective at scale. If our problems are systemic, our solutions must be systemic, full stop.

When I teach classes on this, I often use these two competing metaphors. One is treating people in organizations like plants in a garden. Each plant needs its own soil, its own exposure to light, its own water. You have to take care of every single person to make sure the garden grows well. The other approach is seeing people as water, and organizations like the vessels that hold it. If you shape the organization like a picture, the water will fill the picture. If you shape the organization, like, I don’t know, those silly tuby straws, then the water will fill that shape. If you design an organization where equity and inclusion are easy, where engaging in these inclusive behaviors is so normalized that doing otherwise is hard, you’ll find that people fill that shape, you’ll find that people occupy these norms that you established.

On the other hand, if you have organizations where it’s normal to be engaging in backstabbing politics, it’s normal to be creating fiefdoms and trying to collect things for yourself, it’s normal to try to put yourself ahead of everyone else, I guarantee you, you get me the most inclusive, kind, loving, gracious person in the world, and they will either be forced out in a week, or have to conform to that toxic environment. You cannot change systems by changing people, which is my personal perspective. I’m sure I’ve just picked a fight with every single one-on-one focused practitioner. I’ve heard many times, by the way, you can’t change systems unless you change everyone in them, and I disagree. I very respectfully disagree. I think it’s the other way around, you have to change systems first.

MELINDA: I would say that you have to do both. You have to change systems, and that is extremely important, and I agree that’s often left out of diversity, equity, and inclusion work. And also, there are individuals that shape those systems, there are individuals that need help to understand what their role is in reshaping and recreating the systems. So I do think that there’s an individual component, personally, to that work.

LILY: Yeah, I’d agree with that. I actually got a question in a Q&A just last week after I delivered that diatribe, where someone said: Lily, as a one-on-one focus practitioner, is there a role for me in DEI work? And I was like: Oh God, yes! Like, I don’t want to make it seem like if you do one-on-one focused work, I think you should be smoked from the earth. That’s not correct. It’s that people doing individual one-on-one focused work, in my opinion, need to be really strategic with who they target for that work, who they work with, what stage in the process they work with. I will go out and say that if you’re a one-on-one focused practitioner that thinks you can actually train every single person in a thousand-person organization one at a time, I’m just going to say that that’s bad. I don’t think that that’s how to do the work effectively.

Now, if you’re a one-on-one focused person, and you’re very strategic, and you say, I think I should focus on, let’s say, leaders in this organization, because these leaders take up a lot of resources. If I can convince them to take a different approach to this work, I can get access to resources for a lot of other folks. Well, now, that’s connecting the intrapersonal, the one-on-one, with the systemic. I think that’s extremely strategic. That’s stuff that I can’t do because I don’t work one-on-one with people. But you need to ensure that your theory of change, your framework, is not limited, and I’ll include myself, not just to systems only. Because of course, systems are made of people. And not just to people only, because people make systems. You need to make sure that whatever work you’re doing, it’s deeply strategic, it’s connected to the broader whole, and that what you’re doing actually works. I’ve worked with lots of one-on-one practitioners that somehow get lucrative contracts to train every single person in a company, one-on-one, and then step away from it after five years like, well, I don’t think we did anything. I’m like, then that means it didn’t work, that means you should have done something differently. The answer shouldn’t be, well, time to do it all over again. The answer should be, what am I missing here, how can I do it better?

MELINDA: Yeah, absolutely. So let’s talk about that. Then let’s talk about what individuals can do who want to create change. A good portion of your book is about power and power dynamics. Let’s talk about that first. What are the power dynamics we should be thinking about as we’re looking to improve systems?

LILY: Absolutely. So I have one big chapter about power, and then the chapter after that is how to use power to create movements. But I’ll start from power first. People all have power; everyone has power. One of the questions I get the most is: Lily, if I have no power, what do I do to make change? That’s one of my pet peeve questions, because I don’t think it’s possible for anyone to have no power. Most of the time, people have that thought because they’re thinking about power in a very limited way. They’re thinking about power just as the formal authority that comes from being a manager, or that comes from being an executive. They say, well, because I can’t order anyone around, I don’t have any power.

So I encourage folks to think about power more expansively. There’s many, many different types of it. I go through the typology of power in my book, there’s like six different types, stemming all the way back to the work of two social scientists called French and Raven back in 1930 or something. So it’s definitely not my idea. But there’s formal power: there’s power that comes from authority. There’s also reward power: the ability to give rewards. There’s coercive power: the ability to punish. So these are all relatively normal, people are pretty familiar with them. But then there’s three other kinds of power. There’s expert power: the power that comes from being seen as an expert, from having skill and expertise. There’s informational power: the power that comes from having valuable information in the moment that no one else has. Then there’s referent power, or we can call it charisma: the power that comes from being liked, the power that comes from being respected. Everyone has access to at least one of these kinds of power, and most people have access to several, if not the majority of them. If you are able to build relationships, that’s power. If you’re able to leverage your own knowledge and expertise, that’s power. If you’re able to collect information and use it in really critical moments, that’s power.

So when I help people understand how to use power as an individual, I have to help them understand that it’s not just about getting the promotion to manager and then finally you can do something. There’s so many other things you can do. You can become friends with your manager. You can become seen as a local expert on your team, on issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. You can piggyback off of the expertise of another leader in your organization. You can bring in an external DEI expert. You can make yourself really informed about particular issues that you think are going to become relevant in your organization, so that when the issues actually do happen, you have all the information you need to help. You can build connections with other people who have connections to other leaders. There’s an infinite number of things you can do, to build, to gain, to use power, to make change as an individual. I think it just depends on like, where are you based in the organization? What role do you have? What access to networks do you have? What communities are you close to? What can you do to use your own positionality to enact the sort of change that you want?

This segues pretty well into the next chapter, in which I basically say, now that I’ve talked a bunch about power in this chapter, I’m going to give you a disclaimer. You can do a lot of that as an individual, but no organizational change in DEI happens because of one hero being magically powerful. The biggest change-making movements have been just that, movements! You create power in groups. You create power in communities.

This is another pet peeve I have about the DEI space. A lot of it is about like, use your individual power, use your personal power, secure your seat at the table and become this heroic DEI leader. I’m like, if you’re a heroic DEI leader on your own, it doesn’t matter how good you are, you’re not going to be able to get anything done. You need to create power among community. You need to build movements.

So I have an entire chapter about the different roles people play in movements, how to build a movement that succeeds, how to protect movements against the common ways in which they fall apart. This is a part that’s a little controversial, how to build movements even with people that may not be completely ideologically aligned with you, how to build movements with folks that are in very different parts of their DEI journeys. I spent a lot of time working in organizations that are trying to build movements, and they’re often very insular from the start; they’re started by the most informed, the most educated, the most aware of social injustice, people. And that’s great, it’s super powerful to find three or four like-minded folks. But they always hit up against this wall, they say: we’re only four people, we need 40, we need 400 to shift this. Their approach is usually, how do we change so many hearts and minds that we can change our group of four to 400? I say, that’s not going to happen, you’re not going to create 396 people that are just as eager and excited as you anytime in the next few months.

So your question should instead be, how can we create a movement that’s so compelling, that 396 people with a broad range of awareness, of buy-in, of interest, feel like they should get involved? That’s a tougher question. That’s a question of movement-building, not ideological purity, or not this sort of pie in the sky let’s change everyone’s hearts and minds. That’s what I focus on in the book.

MELINDA: Awesome! So let’s go there then, what are some of the things that you can think about when it comes to using your power to create movements? What are some ways that folks can start to take action, whether it’s a manager or a senior leader, working to create change and working to build a movement around this?

LILY: So if you want to build a movement, you have to know what the movement is trying to achieve, full stop. Like I said in the beginning, the movement is the input, the outcome is what matters. So let’s say you’re trying to build a movement for, I don’t know, pay equity. Let’s say pay equity is the outcome you’re looking for. There’s going to be a lot of people in the organization who want pay equity. Usually, women, people of color, disabled folks, LGBTQ+ folks, folks who worry that they don’t have pay equity. So it would be relatively straightforward to say: Hey, everyone, we need pay equity in our organization to make sure we’re not under-paying people, and so join our movement if you want to make this happen. You’re likely to get some good buy-in from these marginalized communities, because they’re likely not going to be having the best experiences. However, if you just frame it like that, you’re not likely to get much engagement from the folks who are likely to be getting overpaid, or who might be having better experiences and might know it but are ashamed to admit it. So how are you going to engage these people?

Well, what if we shift the outcome from just pay equity to pay equity and also, let’s say process fairness, let’s say structural fair? Let’s say, right now, pay equity or pay inequity is resulting from our organization not being fair, from our organization delivering promotions based on favorability and how much our managers like each other, or like their direct reports. That’s not fair! How can we make things more fair for everyone, such that as long as you’re doing incredible work, you’re getting rewarded for it? Now that’s a fundamentally different movement, that’s framed in very different ways.

You’ll actually find that if you use that kind of framing, a lot of people that may be nominally benefiting from pay inequity will sign onto that. Because they’re just like, well, I like the idea of fairness, like, I don’t want to be unfairly benefiting from things, I want to make something for everyone. But framing something in terms of like, let’s fix this broken system to make things fair, and to achieve pay equity, it invites a lot of people in. It invites a lot of people into that movement and gives people a role in that movement. Versus just saying, like: All right, we’re the pay equity crusaders, fork over your salaries everyone, and if you’re making more than the average, it’s time to deliver the smackdown! That’s not likely to engage a lot of folks, it’s likely to be extremely threatening to a lot of folks, almost guaranteed to ensure that somebody rises up in opposition to your movement and says, no way! Like, if you’re so antagonistic about it, I’m going to sandbag your movement, I’m going to make sure it doesn’t succeed, I’m going to get in your way. So just the framing of a movement can make a huge difference.

But to answer your question, what senior leaders can do, what managers can do? Align on the outcomes. Figure out what it is you’re trying to achieve, and how to rally your team around it. For local managers, for managers who are managing teams maybe not at the VP level or director level, let’s say you’re a line manager who manages five direct reports and they’re all relatively junior, what can you do to support your team? Well, you can still create good outcomes. You can say, I’m in control of relatively few things in this company, but one of them is the team culture that we have among us. How can I create a team culture that is inclusive, that is respectful, where people can disagree with each other, where there’s a really vigorous pool of ideas for problem-solving and relationship-building, where we feel comfortable being vulnerable with each other? That’s an outcome! Great, how are we going to build it?

Okay, well, as a leader, what can I do to model that kind of behavior? What can I do to get my team members excited to build that environment? How can I incentivize the behavior that I’m looking for and disincentivize behavior that goes against it? How can I loop in other leaders in the organization to give me support? I could go on forever about this stuff.

But you focus on the outcome you’re trying to create, you identify who has power to create that outcome—and everyone has power, so what kinds of power people have—and then you create a movement of any number of people, it could just be a movement of one or two, to make it happen. Then you assess whether you’ve gotten to the outcome that you want to. If not, try differently, and try harder. If you have great, congrats, celebrate! Now find another goal and meet that. That’s how the work happens.

MELINDA: Awesome. I just want to circle back a bit on that outcome and finding an outcome that speaks to a lot of people, I think that is extremely important. In fairness, in particular, it’s an intrinsic motivation for somebody versus an extrinsic motivation. We often say, well, the business case shows that diversity, equity, and inclusion can give us these. But that’s not what moves people to become a part of a movement. What moves people to become a part of a movement is something internal, is an intrinsic motivation for change. And we did some research on allyship at Change Catalyst, and the number one motivator for people to do the work to create change is fairness and justice. So it’s so important, I just wanted to call that out.

LILY: I might have actually cited that research in the book, depending on how recently it came out. But yes, fairness is an extremely powerful motivator. Just as importantly, it is one that doesn’t tend to inspire backlash, to the extent that other motivators might, which there’s a lot to be said about how much we should be catering to majority audiences. But I think backlash in all cases is just not conducive, and we don’t want to be framing our movements in ways that literally inspire people to oppose us. Because I mean, DEI work isn’t an us versus them thing. It’s about rectifying these deep inequities and about creating organizations that work for everyone. If people feel like it’s some sort of weird us group versus that group fights, then we can’t get to the outcome that we’re looking for.

MELINDA: Absolutely. You also write about trust in the lack of trust as well, and how that plays a role in diversity, equity and inclusion efforts within companies. Can you talk a little bit about trust and why it’s so important and how it can change what you do within the workplace to create that systemic change?

LILY: Yeah, trust is such a big topic in my book. If anything, it’s one of THE largest overarching topics in my book. I first talk about it in the beginning, where I talk about how a lot of our modern discontent with organizations can be traced back to the fact that we just don’t trust them; we don’t trust what they say, we don’t trust what they do. So when you see companies despairing over putting out a new initiative and getting roasted on social media for it being performative, they say: can you give us a list of behaviors that are not performative and a list of behaviors that are performative, so we can avoid the bad stuff? That’s fundamentally misunderstanding it.

This accusation, whether it’s performative, whether it’s ineffective, all of that stems to whether audiences trust what it is an organization or a person does. If I didn’t trust you and you said: Hey, I’m supporting racial justice efforts by making this donation. I’d say: Oh, it’s a cover, it’s like a front. Like, she’s just doing this to get people off of her scent so that she can keep being a terrible person. Then you can say: Oh, maybe I didn’t donate enough, I’ll donate 20 times more. But I’ll say: Oh, it’s still upfront. So it’s still performative, now it’s just money laundering or some other thing.

Because my actual discontent is not with the amount of money you’re donating, for example. It’s with you and how much I trust you, hypothetically. I don’t distrust you. But I think most organizations and their leaders don’t understand this. They don’t perceive an issue with trust. Instead, they’re just like, well, if they don’t like this action, we need to take a different action. When the fundamental thing that’s broken is their relationship with their stakeholders, their relationship with communities, with employees, with their unions, with their customers. All these things are broken.

So to do DEI work right, especially if you’re in a low-trust environment, you almost have to completely reinvent the playbook. You can’t just follow this linear step of: bring in a consultant, deploy an assessment, develop a strategy, execute on the strategy. If you do all that, you’ll spend a lot of money, only for your constituents to say: Yeah, we don’t trust anything you’re doing, we’re not going to gauge, we’re not going to participate, we’re going to distrust and doubt everything you say.

No. If your big problem is trust, the only way you achieve DEI is by solving distrust. And rebuilding trust takes time, like it takes real commitment. One time I worked with a client, where their biggest problem was, their DEI councils, their employee resource groups, these were all mostly junior employees from marginalized communities, and they did not trust their leadership at all. So their leadership said, it seems like anything we do, you’re going to shoot down. So we’re going to give you resources, what is it you want to do with them? These groups said, we want to get a bunch of programming for us and only us. And their senior leaders got really upset. They said, well, no, we need to benefit everyone, you can’t just use this money for yourselves. The ERGs were like, no, we’re going to use it for ourselves.

And I had this talk with the senior leaders, and I said, you understand that this money that you’re giving them, for them to do things by themselves, sure, it’s not going to benefit the entire organization. But you don’t get to ask that. They are using this money as a token of your goodwill to rebuild trust. So even though it seems counterintuitive, let them do whatever the hell they want with this money, let them benefit their own communities. Because what you’re not seeing here is that money is also being used to rebuild trust. So the next time you engage with them, you can say: Hey, would you be interested in doing something that benefits everyone? And they’ll say, well, the last time you offered us money, you did actually offer it no strings attached, and we were able to protect our communities and to support each other and to help. So yeah, maybe we’ll give it a shot, maybe we’ll try to do something for the other organization or for the rest of the organization.

So it’s this currency of trust that I think most leaders are just completely oblivious to and most organizations completely ignore. I think it’s a real lost opportunity if they don’t recognize how valuable trust is, to both build and gain and use and deploy, and if they don’t have trust, how futile all of their efforts are to try to achieve DEI.

MELINDA: Yeah, absolutely. I want to ask another question that I get asked a lot, which is, how do you respond to people who resist diversity, equity, and inclusion work? How do you move them to action?

LILY: Curiosity, I try to understand why. I won’t pretend like these people don’t exist. There are always people that can never be brought around, that just have a lot of, I don’t know, trauma to work through; they have some internal hates or bigotry or whatever. I think for the people that are like the most lost causes, you don’t change the hearts and minds, you use disciplinary processes to remove them from your organization. If they’re actively harassing people, no! Get on a performance improvement process, and if you’re not improving and you continue to be a horrible person and harass people and be a general unpleasant human being, then goodbye. 95%, maybe 99% of people are not that bad.

MELINDA: Yeah. In our research, we found it’s 3% of the population.

LILY: Oh, that’s great. I love that number. Thank you, I’m going to use that. Okay, so 97% of people are not that bad. Great, I love that my estimate was close. 97% of people are not that bad. So when you work with these folks, I think it boils down to threat. They feel like there’s something they’re losing if they let DEI efforts win, or they’re worried that they’re going to be worse off in some way if DEI efforts succeed.

So if you’re a one-on-one kind of person, you work with these folks to understand what makes them tick, you understand what they’re worried about. In my experience, it’s similar sorts of things. They worry that they won’t have a place in the new organization that’s being built. They worry that they’re going to be unfairly targeted because of their race or gender. They worry that they’re going to be blamed for behaviors that they’re not doing. They’re worried that there’s going to be nothing positive associated with them. They’re worried that they will just have a worse quality of life in the new organization that’s being built. And I think these are all valid fears. I don’t think all of them are completely grounded in reality, but like, they’re all valid fears for people to have.

So you just ensure that movements address them. You ensure that movements make very clearly a space for people from privileged communities, people from majority communities to engage in. You ensure that this vision of the organization we’re building isn’t one where like, I don’t know, all White people have to be self-flagellating to exist in this company. Like, that’s absurd! You ensure that you actively push back against these ideas that like, we’re just replacing the status quo with an inverted relationship between marginalized people and privileged people. That’s the biggest fear. You’ll find that a lot of folks from privileged communities have some understanding that there is injustice, they’re just really terrified of that relationship getting turned upside down, and no one wants to end up on the bottom.

And there’s a lot to be said about why they’re particularly worried about that. But regardless, you can assuage those fears. You can be like: Look, this is what we’re trying to build, this is how we’re trying to build it, this is your role, this is what you can do, you’re really valuable. We need you. We want you. We want to build an organization that works better for literally everyone, and that includes you. And that works. It takes a while, not everyone comes around in a day or two.

Frankly, it’s not for me, I don’t do that kind of work. It’s really tiring. I have enormous respect for folks who work one-on-one coaching, folks who resist and who have a bunch of concerns about the work. Because it can take weeks and months, and sometimes years, to really shift these people. I work with systems. Systems also resist you, just in, let’s say, less hair-pulling ways, in my opinion. So I have enormous respect for the one-on-one folks. But yeah, different people need to be engaging in different work.

MELINDA: Absolutely. We always end with an action step. So I want to ask you, after somebody has listened or watched to this episode and our conversation, what action would you like people to take?

LILY: Yeah. Have a conversation with your team. Have a conversation with the folks who you work most closely with. And ask yourselves, what outcome you wish existed in your workplace? Ask yourself, what could be better here? Then reverse-engineer that to say, how do we make it, how do we create it? How can we leverage our position, our power, our authority, our access to resources, our knowledge, our information? How can we leverage movements? How can we get from Point A to Point B? You’ll likely find that that plan requires people that aren’t in your small group of people that you’re talking to. So now you know how to start a movement, now you know who to reach out to, now you know how to get more folks involved. So just start doing that. And if you need help, there’s tonnes of practitioners out there whose entire jobs are just about helping with certain parts of this process, whether it’s changing systems, delivering assessments, working one-on-one with leaders. That’s what the work looks like, that’s how to do it. You can start it on your own wherever you are, no matter who you are. So get started there.

I suppose, as a second action, buy my book if you want, because there’s a lot of information there. Well, I didn’t want to start with that, because there’s a lot you can do without buying the book. I think just what we talked about today is already super actionable for a lot of people to follow-up on tomorrow, if you want to. The work isn’t rocket science, that’s what I want to convey through the book. It’s hard, but it’s not rocket science. I wanted to put down all of this knowledge that can often be locked away, or gate-kept by practitioners. I just wanted to dump it into a book and be like: Here, take it, just take it, take it and do something with it and fix shit. Because we desperately need our companies and our organizations to be better.

MELINDA: Absolutely, I love it, and agreed! So where can people learn more about your work and your book?

LILY: Yeah, so DEI Deconstructed is out now, you can buy it anywhere books are sold. You can find it on Amazon. You can buy it from a publisher directly, Berrett Koehler Publishers. Then of course, Barnes and Noble, IndieBound, bookshop. Support a local bookstore, if possible. Support black-owned businesses. There’s lots you can do, buy the book anywhere that makes you feel good. On audiobook, ebook, and of course physical hardcover. It’s a really pretty hardcover too, I’m a big fan of it, super glossy.

MELINDA: Love it! Well, thank you, Lily. Thank you, and I’m excited about your book. I’m excited for it to go out into the world to create change. Thanks for all you do and for having conversation with me.

LILY: Yeah, thank you for having me.

MELINDA: All right, everyone, check out Lily’s book, lots more in there. And we’ll see you next week.

We’ll share resources and a transcript from this discussion at ally.cc. And please make sure to subscribe to our channel and rate this show, it makes a difference for us. Thank you for being part of our community.

Remember, the more we take action, the more we grow as humans and as leaders, and the more we transform our communities. So what action will you take today? Let us know your actions by emailing podcast@ChangeCatalyst.co or reaching out on social media.

Leading With Empathy & AllyShip is a show by Change Catalyst, where we build inclusive innovation through training, consulting, and events. You can learn more about us at change catalyst.co. So let’s keep building allyship across our communities and around the world.

Thank you for listening.